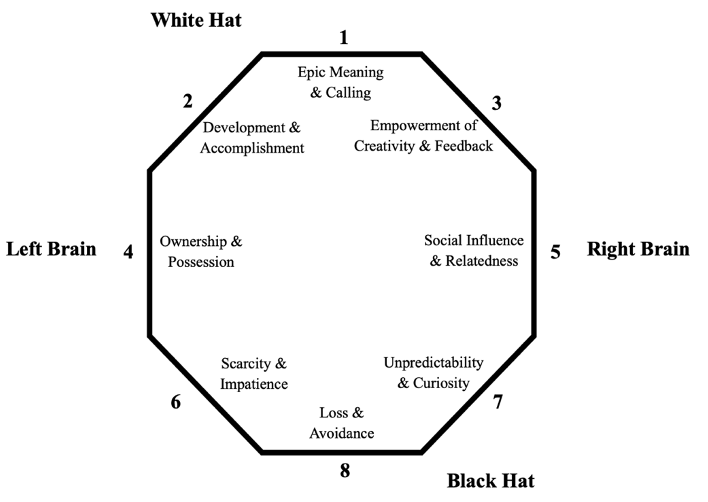

Yu-Kai Chou, an avid gamer since childhood, has developed a structure centred around human motivation for gamifying real life (Chou (2019)). Gamification elements are flexible to address the different goals and personalities of users; Chou (2019) proposes eight ‘core drives’ as the various motivations driving our actions in his framework ‘Octalysis’ below. Are none of the drives present, we will find no motivation and thus take no action.

The above image is explained in the following paragraphs, based on Chou’s (2019) Octalysis framework.

The above image is explained in the following paragraphs, based on Chou’s (2019) Octalysis framework.

1. Epic Meaning & Calling: Feeling ‘chosen’ to embark on something that may be voluntary or for the good of others. Also includes the feeling of ‘beginner’s luck’ or overarching storylines.

2. Development & Accomplishment: The intrinsic drive to progress and reach goals. Achievements and points need to be earned by overcoming challenges. It is the most commonly used drive.

3. Empowerment of Creativity & Feedback: The freedom to express creativity and figure something out yourself, all while seeing the results of your efforts (i.e., through feedback).

4. Ownership & Possession: Receiving something and wanting to better or accumulate it (e.g., avatars or virtual goods). The more time spent on, for example, curating avatars, the more ownership and identification towards it is felt.

5. Social Influence & Relatedness: Social drives, such as competition and companionship. Relatedness is feeling like you belong in a group or acting on nostalgic triggers.

6. Scarcity & Impatience: The freedom to express creativity and figure something out yourself, all while seeing the results of your efforts (i.e., through feedback).

7. Unpredictability & Curiosity: Not knowing what will happen next, you are more inclined to spend time drawing up potential scenarios. Visual storytelling and sudden, unpredictable rewards keep motivation high, because like with gambling, there is always a chance something (favourable) may happen if you continue.

8. Loss & Avoidance: The drive to avoid consequences leading to negative emotions. An example may be quitting and losing all progress or feeling you must act on an opportunity because it may not present itself again.

The White and Black Hat signalise the degree of positivity of these motivators; as you descend the octagon, the core drives become increasingly negative. This, however, does not mean they are inherently ‘bad’ or ineffective; they can be powerful motivators to guide users in the desired direction by giving them a certain pressure to act (scarcity) or to avoid an undesirable outcome (avoidance) (Chou (2019)).

Left and Right Brain do not refer to the true, biological left and right sides of our brain, but illustrate extrinsic vs. intrinsic motivators. The core drives on the left side stem from extrinsic triggers, meaning you are motivated by the possibility of reaching something, of owning something. The right side targets our intrinsic motivation, drawing from social and cognitive desires such as feeling empowered and belonging to a friend group. Ultimately, the difference lies in whether the activity satisfies you (right brain) or the goal at the end of the activity (left brain). Extrinsic motivators, when stopped, have been shown to cause user motivation to decrease to a much lower point than it was before the motivator was introduced; thus, intrinsic motivators may be more sustainable, since they come from within and may persist until after the stimulation is taken away (Chou (2019)).

In summary, the above motivators address our individual needs and goals, finally pushing us to act in a certain way. Varying the use of positive and negative triggers (white vs. black hat) as well as extrinsic and intrinsic motivators (left vs. right brain) is a powerful tool to shape an environment where students are driven, but not frustrated to learn sustainably. Even though the motivators can be segregated into these classifications, they cannot perfectly foresee how people will act. One person may feel motivated to push past their limits, while another cracks under the pressure, and a third finds features such as appointment dynamics and unpredictable rewards annoying and stops playing. Categorising not only game design elements and motivators but also personality types and individual goals is crucial to becoming aware of the different effects one same feature may have on a heterogeneous population. Bartle (1996) has developed a widely used classification for such individual player types.